Mind the gap, the UK is coming apart | Special Issue European Elections 2019

It turns out that Brexit is not the only problem the United Kingdom has to face

South Shields is a coastal town in the North East of England, 280 miles north of London. To get there, one needs to hop onto an old, crackling diesel-powered train, operated by the only state-owned train company of the country. The factory and warehouse landscape outside the window of this train that goes up north reminds passengers of the glorious industrial past of this corner of England. During the Industrial Revolution, the small town of South Shields flourished. Coal mining and a nascent shipbuilding industry made this place thrive and expand all of a sudden. The two World Wars were an additional boost to the local manufacturing, with coal and iron leading arms production. Here, the much-celebrated industrial spirit of the country lived for decades, until the 1980s, when the inexorable decline of manufacturing and mining began. ‘There ain’t nothing left here’ says George, a former steelworker, who was laid off ten years ago by the company he worked for in South Shields. Now he works in Newcastle, less than ten miles to the west of South Shields. He tried to get by living off unemployment subsidies for a while as he was looking for a new job. Eventually he found a role in a waste management company, three pounds less an hour, plus a season ticket to buy every month for the commute. He is sitting at the table next to mine in a café on Newcastle’s high street and clearly feels like having a chat. As Brexit is slowly replacing the weather as a cliché, we inevitably end up touching the issue. ‘They never said how complicated was gonna be to leave, and now if we do leave it will definitely be the end for places like here’.

‘They never said how complicated was gonna be to leave, and now if we do leave it will definitely be the end for places like here’

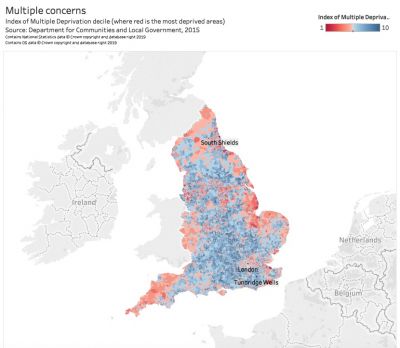

The borough where South Shields is located, South Tyneside, has slightly less than 150 thousand inhabitants. At the same time, it has the unenviable characteristic of comprising some of the most deprived communities of the entire country. According to the Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) elaborated by the government in 2015, a wide range of factors contribute to making life in this area miserable. Many of South Shields’ communities fall among the 10 percent most deprived areas in the county, especially when looking at income, jobs, and health, but also education and skills. Unemployment is a long-standing plight of the whole region. In South Tyneside, unemployment has been well above the national average for over twenty years, with nearly 4 percent of the population older than 16 claiming unemployment benefits in 2017.

From South Shields' coast to Tunbridge Wells

Three-hundred miles south, there is Tunbridge Wells. One hour from London, this time on a shiny new electric train, with patchy but on-board complimentary Wi-Fi. Tunbridge Wells does not have a proud history of manufacturing like South Shields. There are no chimneys in the distance. Instead, it has a past as a fancy, popular place for the aristocracy. Its legacy as a getaway location for the nobles resulted in its name being officially enriched by the prefix ‘Royal’ in 1909, although the attribute is often dropped by locals. For modesty or rapidity, this is unclear. The borough of Tunbridge Wells, with its 116 thousand inhabitants, is located along the luring commuter belt that from London stretches down into the South East, along a railway line that reaches the coast. From the windows, all one can see are fields and sheep, and some middle class-looking towns. Instead of wasteland and disused industrial estates, Tunbridge Wells is surrounded by the greenery of Kent’s countryside, with its orchards and woodlands. The combination of the greenery of the countryside and the convenience of the commute have made the fortune of the borough’s housing market, rather buoyant despite the country’s general slowdown. As an inevitable consequence, house prices have gone up fast, and the number of rough sleepers around here has doubled since 2010. Unemployment here is not an issue: less than 0.7 percent of people above 16 here claim out-of-work benefits.

North and South, Leave and Remain

South Shields and Tunbridge Wells have little in common. This became clear with the EU referendum in 2016, when 62 percent of the people in the borough of South Tyneside voted to leave, while in Tunbridge Wells almost 55 percent supported remain. It appears that the causes of the political cleavage are deeply rooted in the social and economic transformation that have concentrated wealth in London and the South East, while the North began lagging behind. Now, 30 years after the beginning of the North’s decline, it seems difficult to put its economy back on track. The North, since the EU referendum, has almost become a synonym for leave. With very few exceptions, the working-class towns of the North opted for Brexit, likely because of an unsurprising mix of anger and distrust, after an entire economy based on manufacturing was left with no growth prospects. Today, South Shields is one of the many examples of the consequences of a rapid and ruthless process of de-industrialisation that has affected the area. A detrimental combination of the oil crisis, the government monetarist policy in the 1980s, and the push of globalisation saw local companies shut down one by one, and workers being laid off and left wondering whether that was only a passing hiccup of the proud manufacturing history of the North. Turns out, it was not a temporary slowdown.

The North, since the EU referendum, has almost become a synonym for leave. With very few exceptions, the working-class towns of the North opted for Brexit, likely because of an unsurprising mix of anger and distrust, after an entire economy based on manufacturing was left with no growth prospects. Today, South Shields is one of the many examples of the consequences of a rapid and ruthless process of de-industrialisation that has affected the area. A detrimental combination of the oil crisis, the government monetarist policy in the 1980s, and the push of globalisation saw local companies shut down one by one, and workers being laid off and left wondering whether that was only a passing hiccup of the proud manufacturing history of the North. Turns out, it was not a temporary slowdown.

Margaret Thatcher's walk in the wilderness

Many in the North remember Margaret Thatcher’s ‘walk in the wilderness’, in 1987. Photos of the time show the Prime Minister strolling around a dismal wasteland, starkly juxtaposed in a smart suit, firmly clutching her handbag. In the background lies the metal structure of some decaying industrial plant. The local Evening Gazette the following day printed a rather mocking headline: ‘She is here – to see for herself!’. As if that visit could convince London that the risk of the North drifting away was real. Over 30 years later, not much has changed, apart from the fact that the post-apocalyptic piece of land where Margaret Thatcher had a stroll is now a business park. Not far from there, rusty warehouses have gotten even rustier, dominating the landscape of these once-industrious towns. Gone are the good old days when Britain made stuff. Melancholy has slowly given way to frustration and resentment. In over 30 years, no government seems to have managed to relaunch the economy of the North of England. Despite expensive regeneration efforts and considerable amounts of money siphoned into the economy of the northern regions, the local economy has struggled to bounce back. University campuses, retail parks, and the dream of art-based economies have fallen short of driving the renaissance of these places. Durable and sustainable growth requires commitment.

There's more than just the economy

To understand this deeply-rooted divide between the North and the South of England, one of the first elements to consider is labour productivity. Since the crisis, the UK has experienced a generalised productivity slump and so far has not been able to recover to a pre-crisis level. For the country as a whole, this situation of sluggish productivity has been labelled as a productivity puzzle, because it is rather unclear what holds the country back. Yet, productivity exhibits an interesting pattern at the regional level: the areas that once were the thriving industrial motor of the country are now struggling to grow. Labour productivity data across the UK regions and countries shows that London drives the country’s performance, with a productivity 33 percent higher than the average. The South East follows suit. All the rest of the country’s regions are below the UK average. Among the worst performers are Northern Ireland, Wales, and the East Midlands, where productivity is as low as 17 percent less than the national average. As labour productivity is considered pivotal for long-term economic growth (investors, for instance, take productivity into account), the prospects are grim for the North.

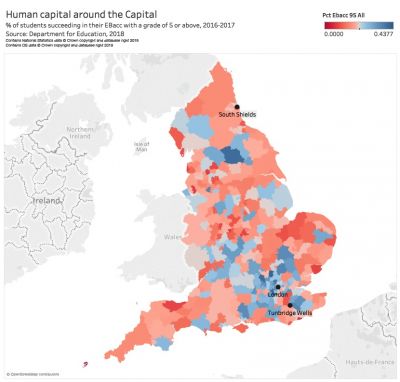

One explanation that has been put forward to try to understand the drivers of the regional productivity gap in the UK is the level of skills and education. Communities in the North struggle because of their low educational attainment levels. Young northerners’ scores at GCSEs, the national exam taken at 16, are below the results of their peers in London and in the South East. The performance of schools in the North is consistently inferior to educational establishments in the South, as reported by Ofsted, the government body in charge of school quality assessment. Then there is brain drain. That talents tend to move from the North to the South of England is a long-standing phenomenon. Yet, it has grown with London’s growing attractiveness for young graduates. Many students move from the South to the North to study in its top-class universities, but then move back as soon as they complete their degrees. This inevitably leaves the North short of highly-skilled workers, and ultimately contributes to the geographical concentration of talent that creates hubs of highly-qualified workers and clusters of unskilled and unspecialised workforce. Skills and education are likely to be intertwined with unemployment levels. Data on claimants of out-of-work benefits show that the percentage of people who receive transfers is considerably larger in the North of the country than in the South. However, there is more. Long-term unemployment, defined as the share of the unemployed that has been without a job for the past year, reaches almost 50 percent in Northern Ireland, but nears 35 percent in the North East and is just below 30 percent in Yorkshire. This is in stark contrast to places such as Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, and Oxfordshire which, with only 13.2 percent long-term unemployment, are among the best performers among all the regions of the European Union.

Skills and education are likely to be intertwined with unemployment levels. Data on claimants of out-of-work benefits show that the percentage of people who receive transfers is considerably larger in the North of the country than in the South. However, there is more. Long-term unemployment, defined as the share of the unemployed that has been without a job for the past year, reaches almost 50 percent in Northern Ireland, but nears 35 percent in the North East and is just below 30 percent in Yorkshire. This is in stark contrast to places such as Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, and Oxfordshire which, with only 13.2 percent long-term unemployment, are among the best performers among all the regions of the European Union.

Low productivity may also have a more practical explanation: infrastructure. A few years ago, the government acknowledged that there was a problem with rail links in the North of England, and the ensuing necessity to modernise it. It established an ad hoc commission, Transport for the North, aimed at studying the feasibility of critical infrastructural upgrades. The pressing need for some investments is clear: electrified trains are still yet to come, and some of the rolling stock used on the routes North of London should be probably better suited for a railway museum. As the Institute of Public Policy Research pointed out in a recent report, in the last ten years the North received around 60 percent less than the South in terms of transport funding per capita. In spite of this, doubts have been cast about the continuation of the HS2 high speed rail link connecting London and the North.

Time to act to bridge the gap

Over the years, governments have started understanding the proportions of the gap. And they started pouring in money for specific projects, without granting fiscal autonomy. With Scotland always considering pulling out, and the thorny issues around Northern Ireland, autonomy is a sensitive issue in the UK. Governments have encouraged closer links among metropolitan areas, neglecting the fact that local synergies may not be enough to attract investments. The commitment to creating a ‘Northern Powerhouse’ (a theme dear to the former Chancellor, George Osborne) or a ‘Midlands Engine’ (asserted by Theresa May, in 2017) made a good impression on paper, yet their outcomes are still difficult to evaluate. Some hints of the North catching up might come from the latest data on Gross Value Added (GVA) growth, the measure of value of production, which show that the northern regions are regaining ground.

Roughly half of the country is extremely exposed to the negative consequences of Brexit

Yet, these weak signs of recovery could be frustrated by Brexit. Analyses before and after the vote have shown that it will be mostly the poor that will pay the price of a disorderly exit from the European Union. High inflation and unemployment are looming threats. This means that half of the country is extremely exposed to the negative consequences of Brexit. Increasing inequalities could only escalate political fractures. The North could become more and more reliant on the South, hindering the whole country’s prospects of economic growth. And with no growth, it is unlikely that the well-being of the people in the North could improve. Margaret Thatcher’s policies that led to de-industrialisation were, at that time, the only viable option for a country that was on the verge of the cliff. Such measures crucially contributed to bringing inflation under control, while laying the foundations for three decades of solid and steady growth that have made the UK one of the most dynamic and innovative economies of the world. However, privatisations and competition brought the North’s growth to a halt. Now is the time to address the imbalance. This is why the government should take the geographical disparities between the North and the South into account in its post-Brexit strategy, because the impact of leaving the EU may not be felt the same across the country. Clamping down on migration from other European countries will not result in creating more jobs where economic potential is low. Instead, long-term investment on improving the workforce’s skills is paramount to ensure that the North’s economy can thrive again.

Clicca qui per la versione italiana ► Il grande divario del Regno Unito

Commenta